More than forty years after the guns of the Civil War fell silent, one battle-worn Confederate rifle was still shooting at Uncle Sam’s soldiers. Although President Teddy Roosevelt declared victory in the Philippine-American War in the summer of 1902, four years later, an insurgent group of Muslim Filipino native tribes known as the Moros continued to do battle with American troops. For centuries, the Moros had resisted colonization by the Spanish, the French, and now the Americans.

In early 1906, on the Philippine Island of Jolo, several hundred Moros armed themselves with a motley assortment of weapons and occupied the crater of an extinct volcano known as Bud Dajo. After attempts to negotiate a peaceful resolution failed, United States troops determined to dislodge the rebels by force. United States artillery barraged the crater before troops stormed their way up the steep jungle hills to then rake the encampment with machine gun fire. Thebattle was nearly a completely one-sided victory for the United States, resulting in the deaths of numerous women and children. The battle was an unmitigated public relations disaster, as some later deemed the battle a massacre.

After the battle, 1st Lieutenant Clifford Leonori of the Eighteenth United States Cavalry was charged with reviewing the weapons gleaned from the battlefield. Among the captured swords, cannon, and firearms, Leonori examined one “old-fashioned Civil War type of muzzle loader” in a remarkably “good state of preservation,” the weapon “still hot from the effect of being fired.” Forward of the hammer on its mottled lock plate, the rifle bore the inscription: ’”Cook and Brother, Athens, GA 1864.”1

During its brief existence, the Cook and Brother Armory in Athens, Georgia, was the largest and most efficient armory in the Confederacy, producing some 6,000 rifles and carbines. More than 40 years after the Confederacy ceased to exist and ten thousand miles away, Lieutenant Leonori found one of these guns “still hostile to the Stars and Stripes.” And “although much worn and bearing the marks of ill use and hard service,” the weapon was “still full of fight.”

A 1917 issue of Confederate Veteran magazine related the rifle’s discovery, albeit with a few inaccuracies and embellishments somewhat characteristic of the magazine. The article claimed that the rifle “had been turned in with the other captured weapons and stored in the arsenal at Manila.” Six years later in1923, author H. J. Rowe attempted to locate this rifle in preparation to write his History of Athens & Clarke County, Georgia. The author wrote to the United States War Department enquiring as to the whereabouts of the captured rifle and subsequently learned that after the battle of Bud Dajo, “useful weapons had been issued to the Islands Constabulary,” while “useless weapons” had been “ordered thrown in the sea.” Unfortunately, his inquiries among the Constabularies of the Philippines “failed to trace the rifle,” and Rowe speculated that the old gun had been cast into the sea off the coast of the Southern Philippine Islands. A 2002 article in Athens Online similarly reported that the final whereabouts of the gun could not be ascertained. It seemed the gun was lost forever.

However, an August 1907 article in the Richmond Times Dispatch, revealed that, in fact, Captain B. H. Dorcy of the Thirteenth United States Cavalry purchased the rifle from the United States Government shortly after the battle of Bud Dajo. In late 1906, Captain Dorcy shipped the firearm to a relative in Richmond, Virginia to present to the Confederate Museum and White House, the former home of Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

Nearly a century after it opened, the Confederate Museum was renamed the American Civil War Museum, and still houses one of the largest collections of Civil War artifacts in the country. Among their inventory is a Cook and Brother rifle, serial number 5455, most likely produced in the spring of 1864 in Athens, Georgia.

Lieutenant Dorcy speculated that perhaps the rifle’s echoes reverberated “on Kennesaw Mountain, disputing the advance of Sherman’s legions; and then a little later in front of Atlanta the smoke from its fiery throat rose to the sky, intermingled with the groans of the dying and the prayers of those that realized they were fighting a forlorn hope.”

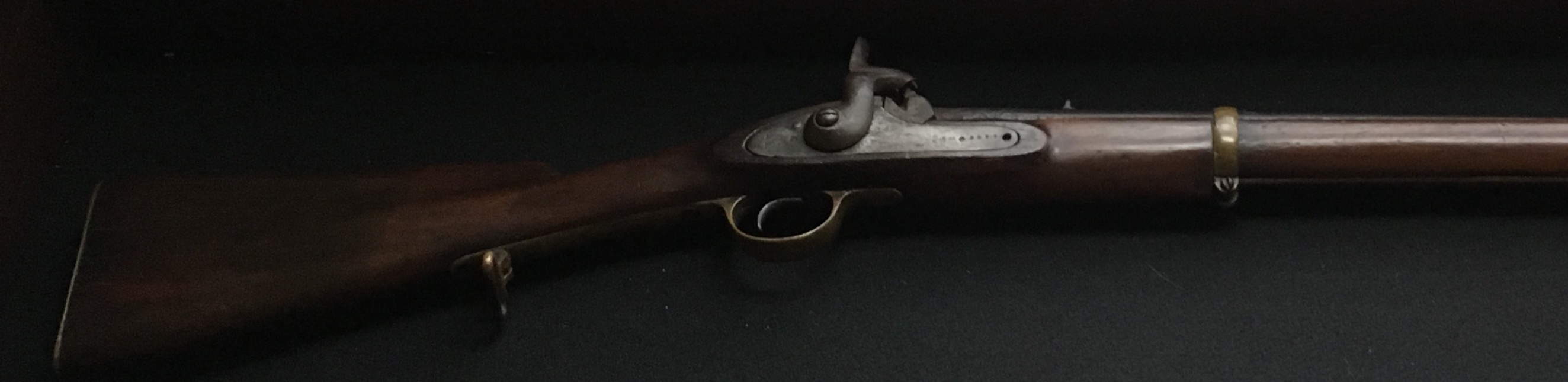

Rifle Number 5455 is a British Enfield Rifle model copy and appears to be Class I Infantry rifle with 33” barrel and 58” overall length. Normally Cook and Brother rifles and carbines only have two brass contoured barrel bands, but on this rifle, three bands clamp the twisted iron barrel to the fore stock. All furniture on the rifle is brass, sourced locally from Athens. Procuring agents from the newly constructed Cook and Brother Armory scoured the northeast Georgia countryside in search of old farming equipment, household brasses, and even church bells to be melted down and re-cast as implements of war in a ‘plowshares into swords’ war effort. How this rifle came to end up in the Philippines will probably never be known, but as one author pondered, “If one had the pen of a Kipling and could make this gun talk, what a romance could be written!”

***The photo at the top is Cook and Brother musketoon serial #5499 in the author’s collection.