Spring comes late to Athens in 1863, and as the war has not yet touched northeast Georgia, the ancient rhythms of the seasons, plowing and harvesting continue much as they have for centuries. Fourteen year old Lemuel Edwards attends church, where rumors swirl of ‘fighting at three places on the Rappahannock,’ and ‘Yankees making another move on Richmond.’ Some congregants prophesy peace in a few months, but most agree that the Northern invaders are not ready to give up yet. All are confident and thankful for the support in their cause “of the Lord and Gideon.”

Spring comes late to Athens in 1863, and as the war has not yet touched northeast Georgia, the ancient rhythms of the seasons, plowing and harvesting continue much as they have for centuries. Fourteen year old Lemuel Edwards attends church, where rumors swirl of ‘fighting at three places on the Rappahannock,’ and ‘Yankees making another move on Richmond.’ Some congregants prophesy peace in a few months, but most agree that the Northern invaders are not ready to give up yet. All are confident and thankful for the support in their cause “of the Lord and Gideon.”

War enthusiasm is at fever pitch, and many of the men previously too old or too young for conscription prepare to enlist. Newly erected breastworks bristle around town, and the newly constructed Cook and Brother Armory imposes on the Trail Creek Branch like a medieval moated castle, complete with crenellated towers. Procuring agents from the armory scour the northeast Georgia countryside in search of old farm equipment, household brasses, even church bells to be melted down and re-cast as implements of war.

Lemuel’s uncle James, stationed in Florida with the Echols Artillery, had written to Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens the previous fall to request a transfer to duty at the Cook and Brother Armory. Though Stephens promptly wrote to Confederate Secretary of War James Seddon to make the necessary arrangements, as yet, James had not been able to wind his way through the Confederate bureaucracy and was still stationed in Florida. Thus far, the only battles he had waged were against sand flies and “mosquitoes big enough to hurt when they bite.”

In addition to helping in the attempt to secure Uncle James a transfer, Vice President Stephens maintains a voluminous correspondence from Liberty Hall, his home in Crawfordville, Georgia. Prior to the war, he had never doubted the legality of secession, only its wisdom. Almost immediately after taking office as Vice President of the Confederate States of America, he and President Jeff Davis had begun to feud bitterly over the proper course for their fledgling nation, and a frustrated Stephens had retreated to his plantation in Georgia. From his study there, the Little Pale Star of Georgia lobbed barbs at the Davis administration from afar. Stephens had formed an unlikely alliance with the malleably principled Governor of his home state, Joseph Brown, due in large part to their mutual disgust at what they viewed as tyrannical acts of the Confederate President.

However, in June of 1863, Stephens makes a rare trip to Richmond to propose to Davis a covert diplomatic mission. War enthusiasm is waning in the north as the casualties mount, and governments North and South have been trading threats of escalating barbaric retaliations regarding black troops and their officers. The prisoner exchange cartel had never functioned well and, after the Emancipation Proclamation, had nearly broken down completely. Stephens proposes to request a meeting with the Northern authorities under the guise of discussing prisoner exchange, with the true purpose of exploring the Northern appetite for a settled peace. With Vicksburg besieged, teetering on capitulation, and Northern war enthusiasm waning, Stephens sees an opportunity to sue for peace. In Richmond, however, Stephens is aghast to learn that Davis, drunk on the victory at Chancellorsville, has already authorized an invasion of the North. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia was already somewhere in Maryland or Pennsylvania, seeking to draw the Union Army of the Potomac into the open, where it could be destroyed. Stephens likewise races north on a mission with very different tactics but the same goal as that of the Northern invasion: an independent Confederacy and peace.

Exact Date Shot Unknown

NARA FILE #: 111-B-1769

WAR & CONFLICT BOOK #: 125

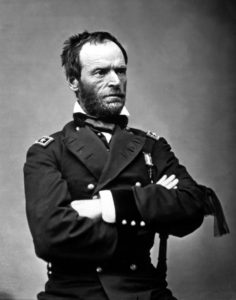

On the march to assist in the siege of Vicksburg, Union General William Tecumseh Sherman is appalled at the “wanton destruction of private property” committed by his troops. Sherman clings to the rules of civilized warfare, but he knows the proud people of the South will not be easily subjugated. The grim-visaged Ohioan endeavors to maintain discipline among his troops, but despite his efforts, many a fine house is laid in ashes. No particular friend to blacks and by no means an abolitionist, Sherman finds himself an unwitting Moses, emancipating slaves as his army rolls through the South, and unenthusiastically commanding black troops. Though Sherman shares the view of many of his troops that the Emancipation Proclamation is “unwise,” the grizzled redheaded General does not question the wisdom of the law; he enforces it without stopping to question why. “All must obey.”

Thus the war between the fledgling agrarian Confederacy and the mightiest industrial power on earth enters its third year. The outcomes of this struggle between two visions of America will have repercussions felt more than 150 years later.